[Updated, 16 March 2025. 2209hrs: new Endnote]

This was the most innovative military exercise I have participated in or witnessed in 22 years of service. Defence Cyber Marvel’s fourth iteration, DCM4, took place in Seoul recently and I had the privilege to attend. If you just want to read about the exercise, skip the intro, and jump to the section headed DCM 4. But first, here’s why I think it matters…

‘The rainbow of colors in the window paints how everything went so wrong, so fast. The water in the Potomac still has that red tint from when the treatment plants upstream were hacked, their automated systems tricked into flushing out the wrong mix of chemicals.

By comparison, the water in the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool has a purple glint to it.

They’ve pumped out the floodwaters that covered Washington’s low-lying areas after the region’s reservoirs were hit in a cascade of sensor hacks. But the surge left behind an oily sludge that will linger for who knows how long. That’s what you get from deciding in the 18th century to put your capital city in low-lying swampland and then in the 21st century wiring up all its infrastructure to an insecure network.

All around the Mall you can see the black smudges of the delivery drones and air taxis that were remotely hijacked to crash into crowds of innocents like fiery meteors. And in the open spaces and parks beyond, tiny dots of bright colors smear together like some kind of tragic pointillist painting. These are the camping tents and makeshift shelters of the refugees who fled the toxic railroad accident caused by the control system failure in Baltimore.

FEMA says it’s safe to go back, now that the chemical cloud has dissipated. But with all the churn and disinfo on social media, no one knows who or what to trust. Last night, the orange of their campfires was like a vigil of the obstinate, waiting for everything to just return to the way it was. But it won’t.’

I remember reading this, August Cole & Peter Singer’s evocative “FICINT” (Fictional Intelligence) opening to the US’ Cyber Solarium report, in Downing Street in 2020. A few years before, I’d read August Cole’s brilliant short story Underbelly, that helps us explore the direct military effects of a cyberattack on the UK. It is no less alarming, resulting in a distributed HQ led by a Special Forces Colonel ‘Fessenden’, having to operate clandestinely, out of a rural pub pulling together the talents needed, with all major bases and MOD cyber networks shut down due to cyber infrastructural attacks. If you can, do read it.

In 2020 I was with our No10 Integrated Review team at a meeting with the Defence Secretary and senior Defence and National Security Leaders. One Treasury official asked what it would mean if we cut the defence budget for aircraft carriers and reassigned it to offensive and defensive cyber. Might we be a more dangerous opponent? Better able to deter, and safer at home? Might spill-over benefits to the wider economy be greater? More nationally resilient?

I don’t think this was a serious proposition, but a challenge – a provocation designed to force people to think. And it is one I have often thought about since. I am willing to bet it has never been seriously and fully explored in the UK.

For me, personally, on issues like the aircraft carriers, FCAS/Tempest, Challenger 3 tanks and all the other totemic and high-end kit that comes up for regular scrutiny, my primary interest is in how we make the decisions on force structures and balance, not what specifically we should have.[1]

Cyber Power debates in Whitehall, like those on Space Power[2], are driven by fundamentally misaligned incentives. Just as air power needed an independent champion to compete equally for resources – the purpose the creation of the RAF served – so cyber and space will never get to make their arguments with full force for as long as they have to make their case through the RAF, Army, RN, or Strategic Command, (at least while Strategic Command is run by officers whose careers depend, in part, on keeping their parent services content).

In fact, for cyber the situation is worse in many ways. Not only does it have to compete with the other military domains of war but it also has to compete for resources with GCHQ. GCHQ’s mission is primarily espionage. As a civilian led and run organisation, it cannot use lethal force, and so cyber-attacks that might cause destruction, death or injury must be carried out by military personnel. But GCHQ is funded by the Foreign Office, not the MOD. The FCDO does not want to hand the MOD an argument taking funding away from espionage to redirect it to military cyber defence and offence.1 Thus cyber, in the sense that August Cole was talking about, never gets to air its arguments for why it should be funded ahead of aircraft carriers, tanks, FCAS, and espionage etc. Our Treasury official’s question remains largely unanswered and unexplored. I don’t think we know how vulnerable we really are. Nor do I think we truly know how much we could do with offensive cyber capabilities if they were fully funded and had an independent champion. August Cole’s cyber FICINT helps us see how we might first learn about our vulnerabilities.

DCM4 is helping ensure our ‘Fessenden’ will be able to find the people he needs to fight back.

Defence Cyber Marvel 4 (DCM 4).

A large hotel in Seoul. Down lifts and up escalators. Into a labyrinthine complex of a large open plan convention centre and surrounding smaller convention rooms and offices. Innovation everywhere. I am shown around this multinational exercise with other visitors, shown what can be done at the unclassified level - the briefings I am given are given to local media, visiting multinational dignitaries, academics, business and industry representatives alike. The capabilities we see are more remarkable for the fact that they are in the public domain.

In one corner a group of soldiers from 2 PARA discuss how they have put together a number of electronic warfare sensors from commercially available hardware. They bought parts on Amazon, on a shoestring budget, with a focus on Counter UAS. They, and Royal Signals soldiers present say these devices are perhaps more effective than those they would currently have access to were they to deploy with the officially provided EW support equipment of the Light Electronic Warfare Teams (LEWT).

Whether the kit itself is better or not isn’t really the point though. As they note, the creation of these devices would enable a proliferation of EW and ISR across the battlefield that is not possible with the current force structures where these capabilities are in high demand and insufficient quantity. The Ukraine war has at times been referred to as the ’24 hour’ war, where technological advancements are only effective for a short period before being countered. Creating a culture in which innovative soldiers can continually develop and refine technological advantage themselves will enable us to maintain the initiative.

It makes me think of the culture inculcated in the Israeli Defence Forces, one of Ein Beira, or ‘no choice’; of tinkering and trying and taking risk, modifying kit, solving problems. It sits in damning contrast to the process of building under maximal regulation, assurance, validation and verification. This has long suggested to me that we have unintentionally killed the tinkering innovation spirit in our armed forces outside these bands of dynamic volunteers and novel thinkers. We have built a culture where the soldier, sailor, airmen and women are expected to passively wait until the kit he or she needs is handed to them with a training manual. As Bernard Schriever wrote of the US DoD in the 1960: “the system now runs the people”. DCM 4, it seems to me, is an antidote. And the PARAs seem to be thriving with having been given permission to innovate, to test and try, in hardware and software – not things we traditionally think of as Parachute Regiment specialities, and a reminder of how capable so many in our Armed Forces are.

In another corner, a young RAF Officer speaks passionately about how much she is learning, how she, and over 1000 participants from 60 different organisations, including 27 nations working in 20 worldwide locations, are mostly volunteers. All are self-taught. They have given up evenings and weekends to learn how to become hackers – they did this outside of military time. Now she is leading a team of Brits from the RAF and Americans, competing against teams from other services and other countries; and also, fascinatingly, other UK Government Departments. The Ministry of Justice has a team here. The NHS too. The Met Police and National Crime Agency. There are teams from across the UK military, though Army personnel and units dominate, since it is primarily the Army, through the Army Cyber Association, that organise the Exercise. Here too are representatives of most of the largest tech firms both globally and in the UK. All compete equally. The strongest performers are not always the teams you’d expect. But the Exercise organisers protect everyone, keeping results - bar those of the teams that win -between them and the teams. The focus is on winning, but also on learning from failure, so any embarrassment must be minimised.

Four and Half Bad Days in Cyberspace

The teams spend 10-months organising and preparing for what they call 4.5 bad days in Cyber Space. They are organised into small rapid reaction teams on the ‘Blue Team’ side. They are tasked with defending unfamiliar networks and systems – from Enterprise IT systems to sophisticated industrial control systems and transport networks on which nations are dependent. There is a large ‘Red Team’, ramping up attacks on them that Blue Teams must defend against, growing in intensity and sophistication as the exercise goes on. A ‘White Team’ provides quantified and objective feedback on performance. There’s a leaderboard. A ‘Green Team’ builds the safe training area competing teams operate in before then defending the whole exercise from real-world cyber-attacks and espionage from outsiders. There are numerous ‘side quests’ – innovation experiments in which the Paras were engaged.

The Green Team is led by a young Army officer. She describes how her all-volunteer team has spent the past 10 months designing and building on the NATO “Cyber range”, essentially a server rack in Estonia within which they have ‘Deployed Infrastructure as Code’ – which is to say they have systems that exist electronically exactly, or as close as possible, to their form in the real-world. Now it is built her team spends their time keeping the network operational while watching for suspicious traffic on the network. If anything looks like it shouldn’t be there, they train to both defend and attack.

The Cyber Range shows how satellites can be hacked, and how not to make this obvious. For example, turning a satellite’s solar power arrays to face away from the sun, leading to a gradual loss of power and functionality that isn’t obviously a cyber-attack. There are lots of ways this might happen – so harder to detect and very effective. They can get a weather camera to misreport, leading to the satellite operators using it at times when the weather makes it less effective, or to choose not to use it when the weather is optimal, because they believe its view occluded by weather [reminder, this is all public domain: see also the DoD’s GitHub ‘How To’ Guide. on satellite hacking, or this online hack-a-sat competition to hack satellites].

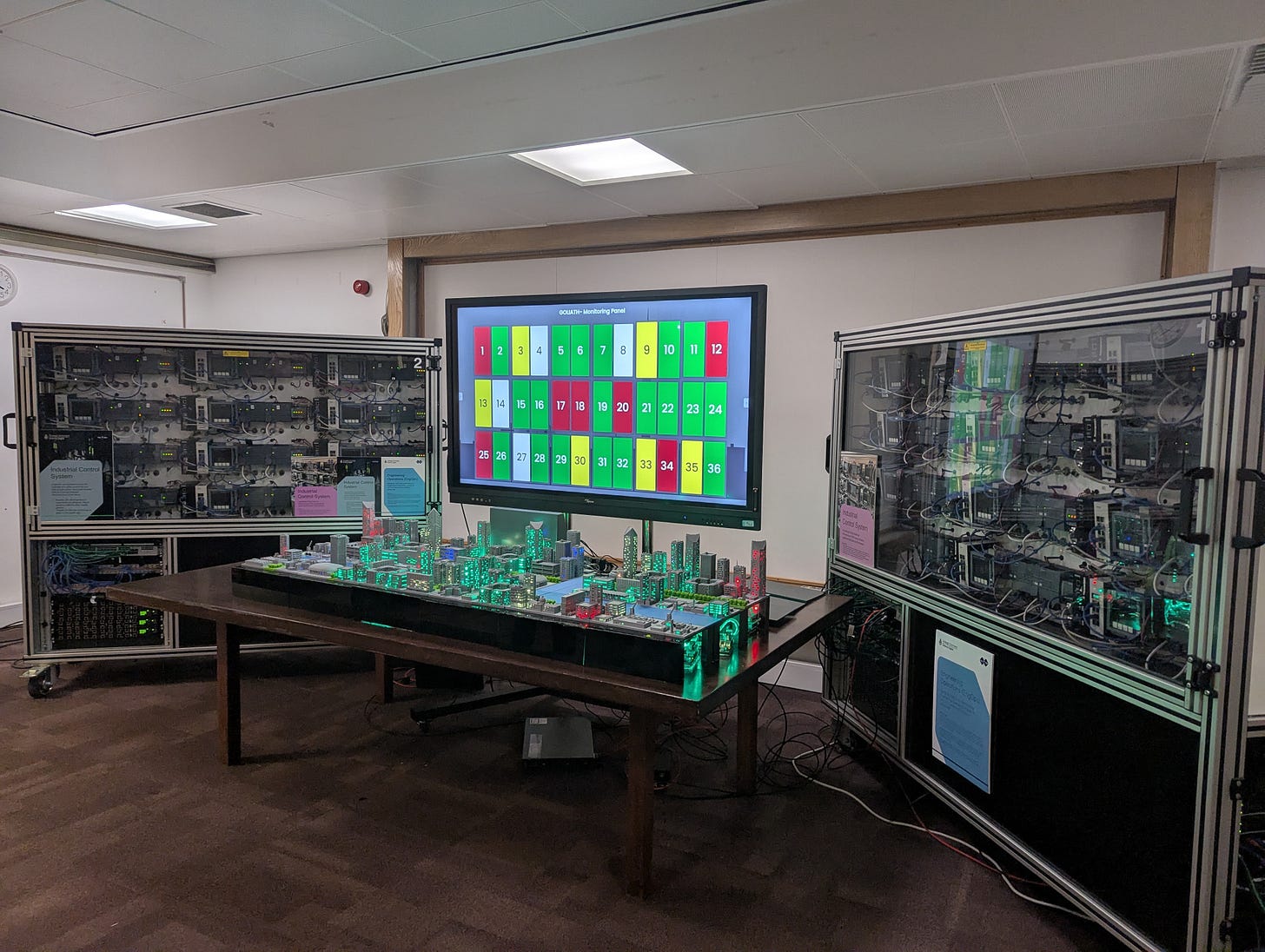

The Cyber Range has vulnerabilities in industrial control systems and simulated military command and control networks. They have ‘real systems’ hardware that you might find in a hospital, or alongside train tracks, and players can try to hack it. Sometimes these are linked to wider simulations of, for example, a whole hospital, or a wider power grid. Sometimes digital targets are linked to models – for example, an aircraft carrier or a Hornby-like train set – so you can see the effects of their being hacked on the scale model or the wider simulated system. Sometimes this can find real-world vulnerabilities, something that the exercise organisers are careful to ensure are reported correctly, and knowledge of which is kept contained. The whole team tests and learns while teaching others on the exercise. It is hard not be impressed.

In another corner, a team is hacking a commercial satellite – a real one – hired for this purpose by the exercise organisers. The satellite is, in the exercise, an adversary’s surveillance satellite. The team on this side quest insert malware so they can watch the enemy through their own surveillance satellite.

Another side quest: a team set to sinking an aircraft carrier – fortunately not a real one this time. The team first gained access to the ships GPS, making the crew uncertain as to its location. They make the ship ‘think’ and report that it was many miles from its real position. Next, the team hack/access the control systems, sending its engines into overdrive and send the ship circling on full power. Turning at full speed causes the ship to list hard. Next, the team, deep inside the ship’s systems, order its ballast system to shift weight rapidly within the hull. Combined with the listing, the carrier passes the point of no return, rolls, and sinks.

There’s an AI Defence Challenge – prompt injection attacks lead another AI to churn out wrong answers, subtly or obviously, or to generate misinformation, or propaganda. There’s drone hacking and spoofing. Teams from all over the world have trained LLMs to play poker. That might not sound like the fare of war, but it has very relevant attributes: incomplete information; uncertainty; a mix of objective and subjective probabilistic assessments – what cards might my opponents have and what might they do?; recursion – what does my opponent think I might have and do, what do they think that I think that they might do, and so on; and of course the staple of the nature of war – chance[3]. The poker competition was won by the Japanese Maritime Self-Defence Forces (the Japanese Navy). The point here is to begin experimenting with AI decision systems. The first time I have seen this get serious attention on a military exercise, even if it is as a side-quest and game.

I'm told that at last year’s DCM3 the exercise incorporated quantum computing, running an air defence scenario, and using quantum (presumably annealing/combinatorics) for ISR planning & execution, and logistics planning optimisation. This year some early experimentation with quantum radio frequency detection has been seen, something to be expanded on in future exercises.

I head to another stand where a rifleman describes his Rifles’ Cyber Teams and the experimentation they are doing supporting tactical actions with cyber support. Inspired by DCM – they are now using Notebook LLM for briefings and analysis, and Google Threat Detection as part of their workflows, with aspirations to widen the use of such tools from tactical experimentation into their headquarters processes.

Across the exercise there are competing priorities for the Blue teams. Keep the hospital system up and running to save lives or shut it down to protect patient data integrity, knowing that if someone gets into your patient data, you might never be able to trust it again? Treatment itself becomes a threat, if you don’t know your patient’s medical history. Teams are constantly called on to prioritise. The attacks they face include new, novel, cutting edge techniques – perhaps something seen just once or twice globally before – exposing the defenders to these emerging threats to ensure they are ready to face them in the real-world should they come calling.

One of the insights I leave with is that a truly intense cyberattack on the UK, or the UK military, is not something we can defend in the way we might try to hold a frontline, or how we might achieve complete control of the air. However long a border in the physical battlespace, the attack surface in cyberspace is simply vast in comparison. As a result, in a cyberwar, we will be hurt – a successful defence can only reduce harm. Maybe the waters swirling around Washington, the crashed delivery drones, the displaced military headquarters operating from a pub – all these ‘defeats’ in August Cole’s dystopian stories were in fact the losses we accepted, as we kept incubators in neonatal wards running, and defended our nuclear power stations and submarines from cyber-attack.

Destroy & Degrade. Reconstitute and Rebuild

The exercise’s organisers are proud of what they’ve built, and rightly so. As they say, you can’t build an effective Navy by staying in the harbour. DCM 4 gets UK military talent preparing for the wars of the future. The breadth of the teams entering, from across industry, defence, public sector and across countries, makes the training unique and the connections for all parties hugely valuable. These are the people they would fight alongside in a real ‘cyber war’.

DCM aims to increase the skills of everyone involved, and succeeds brilliantly. The teams defend systems and attack them, seeking to destroy, degrade, reconstitute and rebuild them. Everyone involved says there is nothing else like it. It succeeds in part because it is not a formal military exercise. Run by the Army Cyber Association, - set up by soldiers who wanted to enjoy cyber similarly to way the British Army funds others to row the Atlantic - and all by volunteers, it has freedoms that would never be granted to a formal exercise. It can be less deferential to organisational fiefdoms – wrapping cyber offence, defence, civ, mil, industry, espionage and international participation without having to do quite so much politicking across those misaligned incentives.

In DCM4 there are echoes of the early innovative days of the RAF, which I wrote about for the Wavell Room in an article they titled: Saving the Royal Air Force. That article described how private contributions, media campaigns, contests and clubs were instrumental to building the capabilities the RAF would later need, creating many of them before it existed, allowing the nascent RAF to harness them rather than having to build them from scratch. Furthermore, contributions, campaigns, contests and clubs created groups who could pressure Whitehall and the Ministry of Defence to act on Air Power, giving them the evidence, showing how powerful it could be, and building public pressure for proper investment. In an age when budgets are even more tightly constrained than they were in the 1930s – with welfare bills and health spending more tightly tying the hands of the state - a similar approach – using clubs and media campaigns, contests and private contributions on cyber, space, electronic warfare and uncrewed systems might be the only way to prepare. The incentives in the system to go slow and under-allocate on all these vital areas are just too strong.

The intrinsic motivation of all involved to improve their skills and put on a world-class exercise is why it works. Formalise it and you’d kill that intrinsic motivation, get rid of the freedoms and the innovation would go.

On the other hand, the exercise as-is needs some formal approvals from within the MOD if is to be allowed to go ahead. As it grows, these are becoming more challenging to win. It needs approvals for cyber reserves that wish to participate to mobilise and join, it needs approvals to win budget whether as a ‘sport’ like rowing the Atlantic, or some other capacity. Likewise if it is to be able to get the soldiers, sailors and RAF personnel released from their day jobs to join as volunteers, it needs some official standing. Partly because of its success – it’s hard to compare it now to a small team rowing the Atlantic to justify funding and approval – and in part because it is so innovative - these can be hard to win. It doesn’t fit neatly into boxes – it isn’t a formal exercise and yet it is vast. It hasn’t been through the normal processes of training needs analysis and multilevel authorisations, sign-offs and so on. These things would likely kill it, but they are in place for a reason. It seems unlikely the exercise can continue as it is. The organisers seem genuinely worried as to whether DCM5 will be approved in time to be put it on next year, or at all.

Yet this year’s Exercise was put on with the full support of the South Korean Government. It attracted Foreign Office funding. Far more people applied to participate than the Exercise could accommodate.

Perhaps the lesson is to fund DCM through its fifth and sixth incarnations, but not seek to control it. Meanwhile to take inspiration from it in the formal exercise programme, and seek to match or exceed the levels of innovation it achieves. If this can be done, the organisers would likely welcome the chance to handover to the big green machine of military bureaucracy, knowing the fire of innovation they have lit is spreading, and being enabled to burn brighter and longer, wider. But it should be for them to decide the time to do this, when they judge the flame has been passed on, and they need no longer keep their torch burning.

Until then, Defence must find a way to ensure DCM4 continues to thrive as DCM5, DCM6, largely as-is. I don’t want to make this seem simple. All those rules and regulations and controls are in place for a reason. But find a way we must. It will need top-down leadership to succeed – it is in the middle-ranks of the military that the flame of innovation dies. Not because the people are bad, but because usually everyone with responsibility over some aspect or another of an exercise has to say yes, and only one person has to say no. Because if DCM goes well, those middle-level approvers will get no credit. But if it goes wrong, they will get the blame. And because absent a Cyber Service looking to drive the capability to excel, to win resources in the next SDR, there is no champion at the top without some significantly conflicted incentives.

For me, personally, I was extremely proud of to see UK Defence being as innovative as everyone knows it can be, but rarely is. To hear the passion of those involved, and watch them pushing boundaries and better preparing us for the future, was genuinely inspiring, and hopeful.

The exercise felt to me like it was an incarnation of ‘the Science Super Power’ agenda and the Indo-Pacific tilt we wrote about in the 2021 Integrated Review. But it was also explicitly inspired, it’s organisers tell me, by General Richard Barrons’ Warfare in the Information Age (WITIA) paper, published in 2016, but originally written and circulated as his internal paper and idea, in the years prior. That paper called out the growing threats and opportunities cyber warfare was creating, as a capability in its own right, but also, crucially, showed the need to integrate cyber warfare in everything we do.

Watching and listening to the personnel on this exercise, I think we have found the generation who can usher in the vision provided in General Barrons’ paper, make it a reality. But, if they are to succeed, Defence Cyber Marvel and its volunteers will need more support to overcome the innovation-stifling institutional pressures, the misaligned incentives, that have prevented us getting there in the ~15 years since the vision for Warfare in the Information Age, was first sketched out.

nb. with apologies to those that were kind enough to speak to me during my visit: I have chosen not to name anyone for security. I am, however, hugely grateful to you all for your time, insights, and commitment to excellence. You really were genuinely inspiring.

[1] This is not to pretend I don’t have views, but I feel much more strongly about the need to improve how we plan and build for the future than any individual kit decision – debates around which are nearly always narrowly single-service dominated, dominated by discussion of what was, and to lesser extent what is, rather than what-will be, and selective in both the evidence and logic used to defend or attack them. I find these debates mostly unproductive and distracting.

[2] Dolman, E.C., 2009. Victory through Air Space Power. Strategic Studies Quarterly, 14(2). Available at: https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/SSQ/documents/Volume-14_Issue-2/dolman.pdf [Accessed 10 March 2025].

Fletcher-Jones, C. (2024). In Favour of an Independent Royal Space Fleet: The Smuts Report and the Precedent of the Royal Air Force. The RUSI Journal, 169(1–2), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2024.2359405

[3] AI is already super-human at poker see Libratus & Pluribus, and like in chess, AI is changing the way humans play the game, with a growing dependency on machines for training and in competition.

New Endnote. 12-03-25.

To be more correct here, in response to helpful constructive criticism:

GCHQ is funded via the Single Intelligence Account [see latest - Cabinet Office Corporate Report 2023-24, Security and Intelligence Agencies Financial Statement 2023-24]. It states:

“The Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs is the responsible Secretary of State for SIS and GCHQ[footnote 2] and the Secretary of State for the Home Office for MI5[footnote 3] The Agencies ensure that the appropriate Secretary of State is briefed on matters that could become the subject of Parliamentary or public interest and on issues, which they need to be aware of in discharging their wider Ministerial responsibilities. There are well-established arrangements for seeking Ministerial clearance for operations when required.

In line with the responsibility assigned to AOs in Managing Public Money the Principal Accounting Officer (PAO) acts to ensure that the SIA operates effectively and efficiently in support of national security policies, aims and objectives. The Deputy National Security Advisor (DNSA) Matthew Collins was delegated as Temporary Acting Principal Accounting Officer for the SIA given the Cabinet Secretary’s medical leave between October and December 2023. The Heads of the Agencies are each AOs in their own right, with delegated authority from the PAO.”

The point remains unchanged, ‘cyber’ as a capability and domain* must compete not only with the the Army, Navy, and Air Force for funding within the MOD, but also with GCHQ. GCHQ has other budgetary champions in Whitehall - where the Foreign Secretary’s responsibilities, as described above, usually make him/her the main lobbyist for GCHQ in Spending Reviews, Defence and National Security Reviews etc.

There are other senior champions for GCHQ, as can be seen in the latest corporate report. Altogether we can see that these are:

The Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs;

the Cabinet Secretary;

the National Security Advisor (or his Deputy at present, since the NSA is a Spad not a Civil Servant);

the Home Secretary [since the National Cyber Security Centre, which solely does Cyber Defence but does is funded through GCHQ. As the GCHQ’s website states “The UK's cyber security mission is led by the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), which is a part of GCHQ.” Which always amuses me because you could delete ‘which is a part of’ and insert ‘which is subordinate to’ and then you’d have a clearer statement of why this needs to be written at the top of the page. In any case, the Home Secretary, for whom making sure nothing awful happens in the UK is the main job, is therefore also a champion for GCHQ, if she/he wants funds to flow down to NCSC rather than to some competing priority elsewhere in Whitehall].

In addition to which, as the SIA financial statements put it the …Agency Heads have a statutory duty to provide annual reports on the work of the Agencies directly to the Prime Minister… giving GCHQ direct access to the Prime Minister to argue for more funds.**

Given all this strengthens the point I am making, rather than weakens it, I haven’t reworded the main article.

*whether it is a domain is a whole other important debate, but I am drawing the line here because (a) for practical purposes in the context of my argument I think it does not matter and (b) I will end up with endnotes on endnotes.

**in adding this new Endnote, I feel like I also add a tone overly critical of GCHQ - I do not intend this. The point is just to be more technically correct in support of my point that ‘cyber’ as an offensive and defensive capability, lacks a truly independent champion of the standing of the Chiefs of Royal Navy, Army and Royal Air Force, and also has to compete with an organisation focused primarily on intelligence gathering.